In December, the Aconcagua season begins. It is the highest mountain outside the Himalayan range, reaching nearly 7,000 m in altitude and, in a way, relatively close to Brazil. Both experienced mountaineers looking to reach new summits and newcomers eager to experience a high-altitude mountain embark on this journey. The problem is that many of them do not fully understand what this means and what truly awaits them. Consequently, we start receiving news—both good and bad, truthful and sensationalized—about what people go through in this harsh environment, where life (human or any other living being) cannot be sustained permanently.

Aconcagua Climb – Photo: Grajales Expeditions / Grajales.net

What Happens to Our Body at High Altitude?

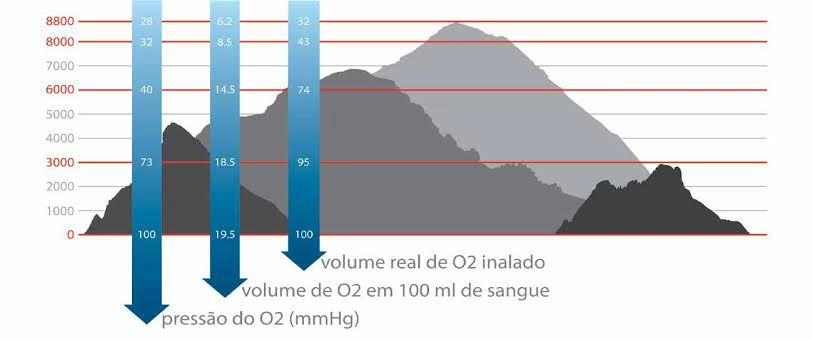

The higher we climb, the thinner the air becomes, meaning oxygen pressure drops, its molecules disperse, and they become less available for our lungs to capture. In simple terms: breathing becomes difficult. If we were at 8,000 m inside an airplane and the cabin suddenly depressurized, we would lose consciousness within seconds.

So, how does someone climb Everest without oxygen? By undergoing a process called acclimatization, where the body gradually adapts to the lack of oxygen. Each person has their own acclimatization time, and this process can take days or even weeks, depending on the target altitude and individual physiology.

However, in this article, we will not discuss acclimatization but rather what happens when our body starts feeling the effects of oxygen deprivation or when acclimatization does not occur as expected, leading to Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS)—from its mildest forms to severe conditions that can be fatal.

What Is Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS)?

There is a significant debate about what qualifies as a high-altitude mountain. It is common in the mountaineering community to refer to altitude when above 4,000 m, but for our body, 3,000 m already represents physiological changes.

Some people are more sensitive and may experience symptoms such as headaches and nausea at just 2,500 m—these are typical signs of Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS). The incidence of AMS varies depending on the logistics of the climb (faster ascents tend to have a higher incidence, both of mild and severe cases). The highest incidence occurs between 3,500 m and 4,500 m, perhaps because this altitude is quickly reached by climbers before beginning the acclimatization process. In the French Alps, for example, there is a high incidence of Acute Mountain Sickness, as mountains between 4,000 m and 5,000 m are often climbed very quickly.

Symptoms of Altitude Sickness

Altitude sickness is a collection of symptoms that typically appear hours or days after reaching high altitude as a response to the body’s adaptation to oxygen deprivation. Its diagnosis is clinical, based on symptoms. The intensity and number of symptoms vary from person to person, and the most common include:

- Headache;

- Weakness and/or fatigue;

- Nausea, vomiting, or loss of appetite;

- Dizziness or vertigo;

- Insomnia or a feeling of suffocation at night.

Risk Factors for Developing AMS

According to the UIAA (Union Internationale des Associations d´Alpinisme – International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation), there are several risk factors for developing AMS (Acute Mountain Sickness) and its severe forms, High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) and High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE). These include:

- Ignorance of the need for acclimatization;

- Rapid ascent;

- Previous history of AMS, HAPE, or HACE;

- Ignoring initial symptoms;

- Dehydration;

- Age (people over 65 are three times more likely to develop HAPE). There are also characteristic altitudes for each condition, with AMS being more common above 2,500 m, HAPE above 3,000 m, and HACE above 4,000–5,000 m.

Oximeter, a device that measures oxygen saturation

The Lake Louise Score

The table of signs and symptoms, known as the Lake Louise Score, allows you to track symptoms at each ascent and their intensity, with each receiving a score from 0 to 3. The sum of these scores will determine if you have Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) and its severity:

- Less than 3 points: No Acute Mountain Sickness (or it is still insignificant)

- 3 to 5 points: Mild AMS

- 6 to 9 points: Moderate AMS

- More than 9 points: Severe AMS

To confirm an AMS diagnosis, headache is a mandatory symptom. Although the table is recommended for researchers and scholars rather than as a diagnostic tool, it is widely used by mountain guides, even though it does not replace a proper clinical evaluation.

Treatment for Acute Mountain Sickness

The primary focus of treatment is symptom resolution. One of the drugs used for both prevention and treatment of Acute Mountain Sickness—well known among high-altitude practitioners and even considered doping by some—is Diamox (whose active ingredient is Acetazolamide). However, it is merely a diuretic that has the side effect of acidifying the blood, causing increased breathing to balance blood pH. This means that by breathing faster, we take in more oxygen, whether during the day or at night (when respiratory rates decrease during sleep, leading to more hypoxia and worsening symptoms—hence the recommendation to “climb high and sleep low”).

Since Acetazolamide is a diuretic (a medication that increases urine output), it is essential to increase hydration, which is crucial for both preventing and improving AMS and its severe forms. It is also important to note that at high altitudes, increased metabolism, combined with dry air and exertion, already leads to greater fluid loss than normal.

Ideally, before embarking on an adventure, consult a doctor experienced in high-altitude conditions to receive guidance on procedures and the appropriate use of medications.

Aconcagua Climb – Photo: Grajales Expeditions / Grajales.net

Severe Forms of Altitude Sickness

Symptoms usually disappear within 72 hours if altitude remains constant. However, if symptoms worsen or the person continues to ascend without allowing proper adaptation, severe conditions may develop, such as High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) and High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE).

High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE)

High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema is not caused by heart failure and has a different mechanism from hypertensive pulmonary edema, though its exact causes are still not well understood.

The main variables—both controllable and uncontrollable—that predispose a person to HAPE include genetic predisposition, maximum overnight altitude, ascent rate, physical exhaustion, body exposure to cold, and recent exposure to high altitudes.

It is a serious condition and should be treated as an emergency. The main symptoms include decreased exercise performance, respiratory fatigue even at rest, and a dry cough. It progresses with worsening shortness of breath, extreme fatigue, and a productive cough with or without bloody sputum. Fever, cyanosis (bluish lips and fingers), tachycardia, low oxygen saturation, and even loss of consciousness may occur.

Treatment involves providing supplemental oxygen and descending as soon as possible. Medications such as nifedipine and tadalafil can be used to prevent progression and as adjunct treatments under medical supervision.

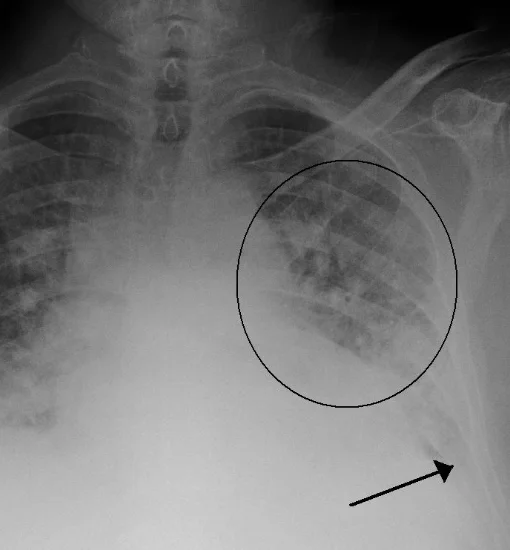

X-ray of lungs without edema

X-ray of lungs with edema

High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE)

High-Altitude Cerebral Edema is a severe and potentially fatal condition. It may start with persistent headache, apathy, withdrawal from the group, and dizziness, progressing to motor incoordination (ataxia) and altered consciousness, ranging from mood and behavior changes to complete unconsciousness.

Treatment includes medications such as Dexamethasone and Acetazolamide, oxygen supplementation, and descent. Proper care of patients experiencing consciousness alterations—or those unconscious—is crucial.

The Importance of Acclimatization and Prevention

Despite its relatively simple treatment and good prognosis, Acute Mountain Sickness can disrupt an expedition’s progress, logistics, or even force its cancellation. Severe cases can put not only the expedition at risk but also the participant’s life. The only and best prevention is proper acclimatization!

Illustration showing the relationship between altitude, inhaled oxygen volume, and oxygen concentration in the air.

Recommendations for Proper Acclimatization

Some recommendations for proper acclimatization include:

- Above 3,000 m, do not ascend more than 500 m per day;

- Spend two nights at the same altitude every two to four days of ascent. You may climb higher during the day but should return to a lower altitude to sleep;

- Climb high, sleep low;

- The use of medications to prevent altitude sickness should be reserved for special situations, such as rapid ascents or individuals with known acclimatization difficulties.

Conclusion: Safety in High-Altitude Mountaineering

To have a safe and more comfortable experience in high-altitude mountaineering, it is essential to understand acclimatization and recognize, prevent, and treat Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) and its severe forms.

Being in good clinical, physical, and psychological condition allows for more efficient acclimatization and better overall performance. Make sure to gather information before venturing into a new environment for the first time. Your chances of success and returning in good health will be much higher.

Bibliographic References

1. Medicine for The Outdoors – The Essential Guide to First Aid and Medical Emergencies – 7th edition – Paul S. Auerbach, MD

2. Medicina em Áreas Remotas no Brasil – Juliana R. M. Schlaad, Sacha W. Schlaad

3. Consensus Statement of the UIAA Medical Commission Vol. 2 – Emergency Field Management of Acute Mountain Sickness, High Altitude Pulmonary Edema, and High-Altitude Cerebral Edema*

4. Altitude Illness: Prevention and Treatment – Stephen Bezruchka, MD, MPH – The Mountaineers Books

This post is also available in: Português (Portuguese (Brazil)) Español (Spanish)